Author: Prof. Dr. Bibiana Grassinger

I am delighted to contribute a paper on intercultural understanding in the final publication of TOGEHTER. It is an affair of the heart for me because today’s students face intercultural encounters again and again. Globalisation means that studying abroad or spending a semester abroad has almost become a matter of course. And even after graduation, all “international” doors are open to students: be it through a job abroad, a job at home in an international company or through the most diverse cultures encountering each other in a company. Intercultural competence is indispensable. You can find numerous publications and even guidelines (books) how to behave in the most diverse countries.

It was natural that the project TOGEHTER was planned in an international context. Ulm’s – and the university’s – location directly on the Danube made it obvious to cooperate with universities that are also located in countries bordering the Danube. From previous cooperation, contacts already existed with the Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek (Academy of Arts) and with the University of Pécs.

From a company’s point of view, intercultural competence is also an important quality: a company’s first foreign markets may be countries bordering its own country. If the company wants to expand further (Ansoff matrix: new markets), e.g. to the entire European market or even beyond, intercultural competence becomes a key success factor. Considering the entire value chain, international supply chains also play an important role. Hence, in recent decades, intercultural competence has become one of the key competences required in a wide range of professions and industries (Deardorff/Hunter 2006, Schellhammer 2018, Hrehová/Seňová 2019).

The original idea for this project, which ran for three years, lies in a “Socrates Intensive Programme” funded by the European Union. Students from universities in four European countries (Austria, Italy, Greece, Spain) met to work on tourism management problems. The programme took place at a different university each year and lasted two weeks. Lectures and group work alternated. At that time – and that was 15 years ago – I was involved as a lecturer, which was very exciting, because the students had different approaches to the tasks and I, as a lecturer, was also challenged interculturally. Interculturality does not stop at the student level, the lecturers and staff of the four universities also cooperated for the tasks and assignments. This experience was very formative for me. For this reason, I had the idea to enable such an enriching intercultural experience to today’s students and lecturers.

Let us now return to culture and interculturality. How can cultures be characterised; how do they differ? According to UNESCO (2001) “culture should be regarded as the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society or a social group, and that it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs”. To look more closely at the dimensions of culture, it is useful to consider the study by Geert Hofstede (1983). From 116,000 questionnaires of IBM employees in 50 countries (two survey dates), he used a factor analysis to determine four cultural dimensions that explained half of the variances:

- Power distance: flat hierarchies or large hierarchical structures

- Uncertainty avoidance: tolerance and acceptance of new and unknown situations or high importance of plans and analyses

- Individualism versus collectivism: What is more important? The good of the group or the good of the individual?

- Masculinity versus femininity: Competition, assertiveness, and material success (masculinity) or cooperation, harmony and equal distribution of roles (feminity).

In later studies, two further dimensions were found (Hofstede et al. 2017):

- Short-term vs long-term orientation: Time horizon of a company – profit in the shortest possible time or building a long-term personal relationship

- Indulgence vs restraint: Indulgence and self-actualisation or restraints

These cultural dimensions explain differences in the responses of test persons from different cultures. Values and patterns of action in individual cultures can be derived from this, but not fully explained. “Intercultural competence means the ability to deal constructively with people from different backgrounds and to cooperate with them successfully and independently. The fact that people’s identity is not determined merely by their origins in a given country, but by a number of different ‘cultures’ and characteristics (e.g. gender, education and profession, age, place of birth and of residence, nationality (or nationalities) of parents, political leanings, sexual orientation etc.) is of a fundamental importance here.” (Hrehová/Seňová 2019)

In the context of the project TOGETHER this also means that it is not only about the cultures of the participating countries Germany, Croatia and Hungary. The different approaches of designers and business economists to a problem can also be explained by different “cultures”.

Let us now have a closer look at the culture dimensions of our three participating countries:

Fig. 1: Country comparison of the cultural dimensions (Hofstede insights 2021)

Figure 1 shows that Croatia is a culture with high power distance, which avoids uncertainty and is more group oriented. The culture is rather feminine; rules and restraint play a big role.

Hungary shows itself as an individualistic and masculine culture, i.e. the individual is more important than the group, and competition is more important than cooperation. Hungarians tend to avoid uncertainty. Rules and restraint also play a big role here.

In Germany, power distance shows low values which means that this dimension is not very important. Individualism and masculinity play a big role but are not as strong as in Hungary. Germany shows the highest value of the three countries for long-term orientation. Rules and restraint also play an important role.

As the figure shows, there are clear differences between the cultures. However, it should also be borne in mind that these are general statements for a country and that deviations in the behaviour of individuals are also possible. The reasons for this can be manifold.

Let us now turn to intercultural competence. There are numerous works and definitions in the literature (Barrett et al. 2014, Anderson et al. 2006, Bennet 2008, Guilherme 2000, Kim 2009, Leung et al. 2014, Ting-Toomey 2005, among others). According to Spitzberg and Changnon (2009, 9), intercultural competence is “the appropriate and effective management of interaction between people who to some degree hold different or divergent affective, cognitive, and behavioural orientations to the world”. Lee et al. (2012, 43) describe the development of intercultural competence as “the ability of individuals to respectfully engage and communicate with others so that they can benefit from the other person’s cultural perspectives”. Deardorff (2006, 249) refers to a widely accepted definition of intercultural competence as “the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations, to shift frames of reference appropriately and to adapt behaviour to the cultural context”.

In Australia, intercultural competence is even an essential part of the school curriculum. In 2016, 49% of the Australian population was either born overseas or had one or both parents born overseas (ACARA 2021). Thus, Australia has placed a strong emphasis on intercultural competence from the very beginning. The focus is on three essential interrelated capabilities:

- Recognising culture and developing respect

- Interacting and empathising with others

- Reflecting on intercultural experiences and taking responsibility (ACARA 2021).

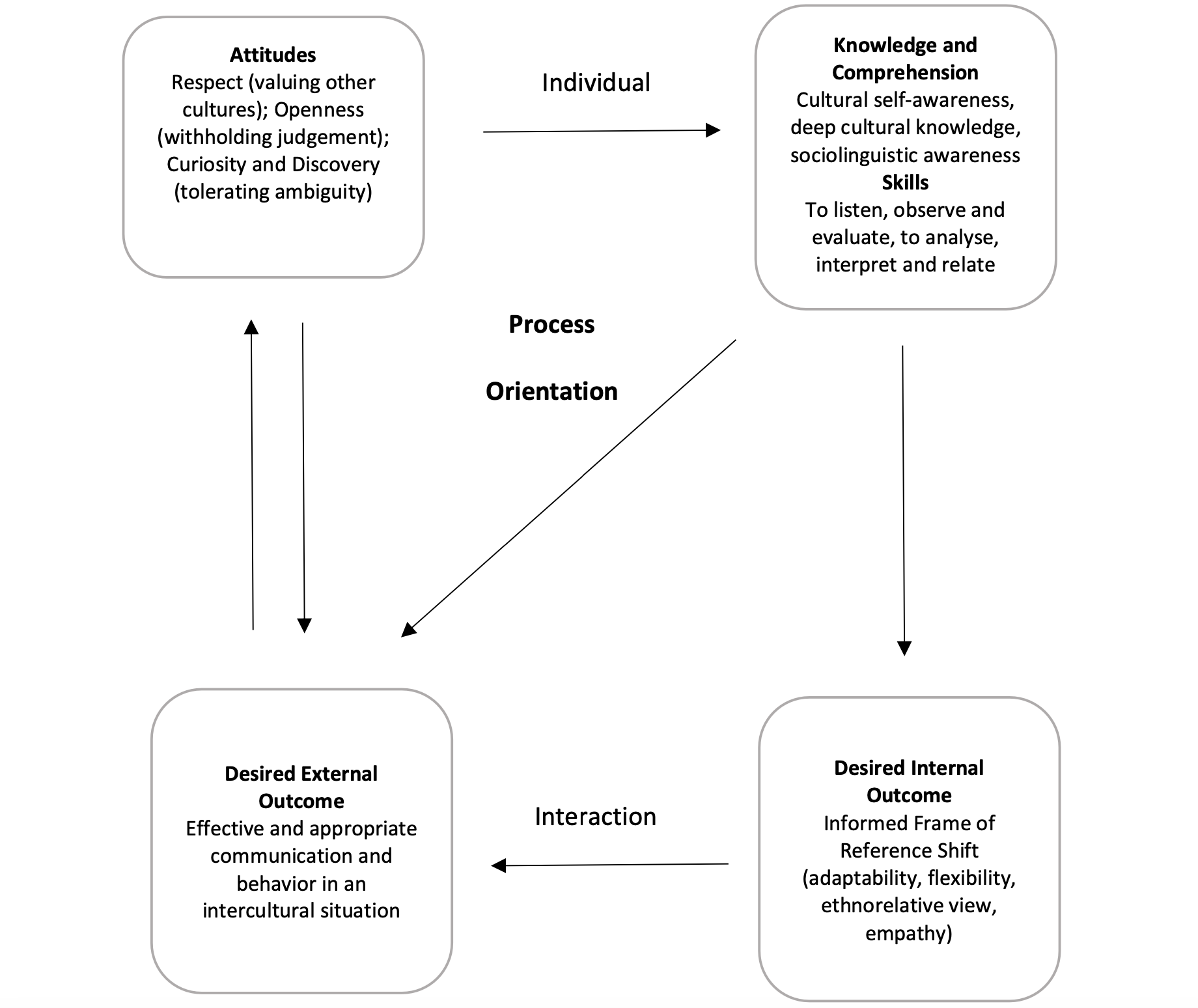

So how can intercultural competence be developed? According to Deardorff (2006), it is an iterative process of life-long learning (“learning spiral”) in which individual values and skills are prerequisites for interactions with other cultures (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Deardorff’s Process Model of Intercultural Competence (own illustration adapted from Deardorff 2006, 256)

Deardorff first looks at the individual person: Attitudes such as respect, openness as well as curiosity and discovery form the basis for intercultural competence. These values are then enriched with knowledge and comprehension (cultural self-awareness, deep cultural knowledge, sociolinguistic awareness) and skills (listen, observe, evaluate, analyse, interpret, relate). Only when Attitudes, Knowledge, Comprehension and Skills are present, one can create the desired internal outcome, e.g. adaptability (e.g. importance of relationships in China), flexibility (e.g. punctuality in Germany), ethnorelative view and empathy. If there is an interaction with a person from another culture, the person will be able to communicate effectively and properly and show appropriate behaviour in this intercultural situation. In turn, values are influenced by action and reaction in a conversation. The stronger the values such as respect, openness, curiosity, understanding and specific skills are, the stronger the intercultural competence is (Deardorff 2006).

Figure 2 also explains that the affective (attitudes), cognitive (knowledge, skills) and behavioural levels (interaction) are addressed. Without this triad, intercultural competence is not possible (Spitzberg/Changnon 2009, Erll/Gymnich 2015).

Let me briefly touch on communicative interaction. The fact that we speak different dialects or languages in different cultures is taken for granted. However, interaction consists not only of language, but also of non-verbal communication (Erll/Gymnich 2015):

- Gestures (movements of fingers, hands, arms, and head).

- Facial expressions (movements of the facial muscles, especially in the area of the mouth, eyes, eyebrows and forehead)

- Gaze behaviour

- Proxemics (the physical distance between the interlocutors)

- Haptics (the behaviour of touch)

- paralinguistic codes (the use of the voice, voice volume, pitch, intonation, etc.)

This means that interpreting gestures, head movements or the physical distance between people in a conversation also counts as intercultural competence. Consider northern Europeans, who maintain a larger social distance than southern Europeans. As early as 1960, Hall noted various conversation distances in different countries.

Intercultural understanding is a process of life-long learning (Erll/Gymnich 2015). Hrehová/Seňová (2019, 234) propose the development of four intercultural competences in order to improve intercultural competence:

- Intercultural motivation

- take interest in current events locally and globally,

- engage with people in your employer organization and community,

- network with diverse communities and organizations,

- recognize intercultural capabilities and seek areas to improve,

- take initiative to explore your environment,

- actively network with people from different cultures.

- Intercultural knowledge

- know how to be diplomatic and sensitive to the dynamics of a culturally diverse workplace,

- understand how to communicate with people who speak or write in a different language,

- know how to adapt to a new environment,

- understand ways to cope with constant change,

- learn phrases in a new language, or learn a new language,

- recognize and respect cultural diversity,

- learn appropriate, effective ways to communicate with people from different cultural background

- Strategic thinking

- consider new strategies during each cultural encounter,

- check for opportunities for cultural growth,

- plan how to pursue networking opportunities with people with culturally diverse backgrounds.

- Appropriate behavior

- recognize and adapt to cultural differences in communication,

- display a positive attitude towards change and new environments,

- show flexibility and explore possible solutions in an innovative and creative way.

All people involved in TOGETHER may check now if they developed or even improved their intercultural competence.

In summary, intercultural understanding is considered a key competence. Hofstede (1984) pioneered the field of cultural dimensions. Deardorff’s (2006) model shows that intercultural competence is not acquired once but should be understood as a lifelong learning process. With the concluding references by Hrehová and Seňová (2019), intercultural competences can be checked: Am I on the right track? Where are gaps? Is there still need for improvement? Graduates starting their working careers in particular can use intercultural competence as a highlight in their application.

Thanks to the careful selection of students by the participating universities, the workshops could start with the best prerequisites. When selecting the students, the lecturers did not only focus on their professional skills, but also on the students’ motivation to work in such an intercultural and interdisciplinary setting. In the end, I am sure that everyone involved in this project benefited: both the students and the lecturers, but also the organisations and companies that were involved in the projects with their tasks. Finally, society has benefited, because many students practised and acquired an invaluable skill, namely intercultural competence. Furthermore, I hope that friendships have been formed that will last beyond the project.

„We should never denigrate any other culture but rather help people to understand the relationship between their own culture and the dominant culture. When you understand another culture or language, it does not mean that you have to lose your own culture.” (Edward T. Hall)

Bibliography

ACARA (2021). Intercultural Understanding. (https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/general-capabilities/intercultural-understanding/ [21.07.21]).

Anderson, P. H., Lawton, L., Rexeisen, R. J., Hubbard, A. C. (2006). Short-term study abroad and intercultural sensitivity: A pilot study. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(4), 457-469.

Barrett, M. D., Huber, J., & Reynolds, C. (2014). Developing intercultural competence through education. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Bennett, J. M. (2008). Transformative training: Designing programs for culture learning. In M. A. Moodian (Ed.), Contemporary leadership and intercultural competence: Understanding and utilizing cultural diversity to build successful organizations, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 95–110.

Deardorff, D.K. (2006). The Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalization at Institutions of Higher Education in the United States. In: Journal of Studies in International Education, 10 (3), 241-266. DOI: 10.1177/1028315306287002.

Deardorff, D.K., Hunter, W. (2006). Educating Global-Ready Graduates. In: International Educator, 15(3), 72-83.

Erl, A., Gymnich, M. (2015). Uni-Wissen Interkulturelle Kompetenzen: Erfolgreich kommunizieren zwischen den Kulturen – Kernkompetenzen. Klett Lerntraining bei PONS: Stuttgart.

Guilherme, M. (2000). Intercultural competence. In M.S. Byram (Ed.), M. Routledge Encyclopedia of Language Teaching and Learning, London and New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 298-300.

Hall, E.T. (1960). The Silent Language in Overseas Business. In: Harvard Business Review. May/June, 38(3), 87-96.

Hofstede insights (2021). Country comparison. (https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/croatia,germany,hungary/, [20.07.2021]).

Hofstede, G. (1983) National Cultures in four dimensions. A Research-based Theory of Cultural Differences among Nations. In: International Studies of Management & Organisation, 13(1-2), 46-74.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede G.J., Minkov, M. (2017). Lokales Denken, globales Handeln. Interkulturelle Zusammenarbeit und globales Management, 6., vollständig überarbeitete und aktualisierte Auflage, beck im dtv, München.

Hrehová/Seňová (2019). The intercultural competence more valuable than ever before. Multidisciplinary Academic Conference (MAC-ETL 2019), Prague, Proceedings of MAC 2019, 229-237.

Kim, Y. (2009). The identity factor in intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 53-65.

Lee, A., Poch, R., Shaw, M., Williams, R.D. (2012). Engaging Diversity in Undergraduate Classrooms: A Pedagogy for Developing Intercultural Competence, ASHE Higher Education Report, 38(2).

Leung, K., Ang, S. & Tan, M.L. (2014). Intercultural Competence, Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behaviour, 1, 489-519.

Schellhammer, B. (2018). Dialogical Self as a Prerequisite for Intercultural Adult Education, in: Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 31(1), 6-21, DOI: 10.1080/10720537.2017.1298486

Spitzberg, B., Changnon, G. (2009). Conceptualizing Intercultural Competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.) The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, Sage, 2-52.

Ting-Toomey, S. (2005). Identity negotiation theory: Crossing cultural boundaries. In W. B. Gudykunst (Ed.), Theorizing about intercultural communication,Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 211–233.

UNESCO (2001). Universal declaration on cultural diversity. (http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13179&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html [21.07.21]).

Bibiana Grassinger is Professor of Marketing and Tourism Management at the IU International University (distance learning and dual studies). From 2017 to 2018 she held a professorship for Marketing at the University of Applied Sciences for Communication and Design (HfK+G) in Ulm. She received her doctorate from the University of Innsbruck. Bibiana initialized the TOGETHER project to provide students with international and interdisciplinary experiences. Her teaching and research activities focus on marketing (branding, communication) and tourism (destination management, sustainability). E-Mail: bibiana.grassinger@iu.org.

Recent Comments